The Médor case study

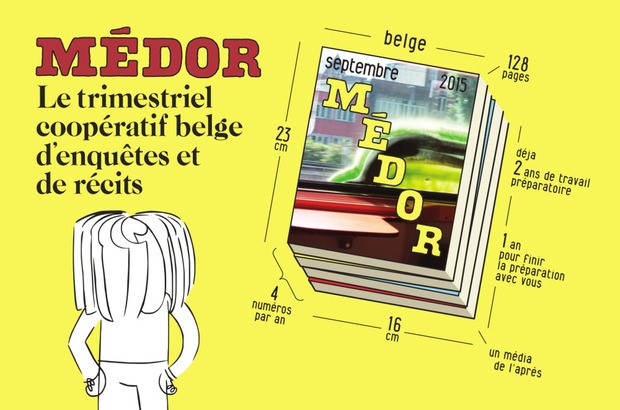

Médor is a quarterly Belgian and cooperative investigative and news report magazine. It was first published in 2015 and has already received a large number of awards in recognition of the quality of its content and economic and social model. We interviewed one of the founders of Médor, Tiffany Lasserre, to get a better understanding of the advantages of the cooperative model in this highly particular and difficult sector, namely that of the journalistic press.

Tiffany Lasserrre is the only founding member who is also a full-time employee of the cooperative. She has been involved in Médor since its very beginning and she is now its head of communication and publication. As such, she is an ideal person to talk to us about the creation of this magazine, which is unique in its kind in the French-speaking part of Belgium.

Indeed, whilst the majority of Médor’s members are its readers and the arrangements for the involvement of the self-employed workers (the journalists) would appear to be of a hybrid nature or even foreign to the typologies of cooperatives represented by CICOPA, their experience resonates strongly with the cooperative model as a tool at the service of the needs of the journalists and an independent press.

The birth of Médor

“The idea of Médor was born in 2012”, Tiffany explains. “The small group of founders, namely the graphic artists and journalists, all got together to talk about their dissatisfaction with their profession. In particular, they lamented the fact that they could no longer go out into the field to carry out investigative work. This was an unsatisfactory situation both for them and for the readers. But rather than just complaining about this situation, they asked themselves what they could do to change it and to propose something new and different. The idea of producing a quarterly publication such as Médor was not born overnight, rather it took several years before it came to fruition.”

In fact, the Médor cooperative was only formally established in 2014: “we spent two years just thinking about the idea and as the group of founders continued to grow, we finally decided that the cooperative form was the best fit for both our project and our values. We then gave ourselves one year to launch the publication. We did not want to throw ourselves into the project without being sure that people would read our publication! So, we spent a year looking for our future readers across Belgium. We organised close to 100 meetings to talk about the project and to ask people in it to pay their 60 EUR subscription in advance. It was a kind of crowdfunding. If the project had not got off the ground, we would have given everyone their money back. Our aim was to have 3,800 subscribers before publishing the first issue, but we quickly realised that this was completely out of the question”, Tiffany explains with a wide grin.

“So, at our first general assembly with the members of the cooperative, we reviewed this figure and lowered it, for 2015, to 1,500 subscribers and a further 2,500 copies to be sold in bookshops. This dual objective was broadly achieved when the first issue came out. It has to be said that efforts were made to censor our investigative piece into the Mithra pharmaceutical company (read here), and that was the best publicity we could ever have dreamed of!”

Médor as a cooperative

When asked about the reasons behind the adoption of the cooperative form, Tiffany replies: “we were drawn to it because of its governance principles and the requirement for transparency. It guaranteed us independence thanks to its principle of “one person, one vote”. We wanted each member to be able to express themselves equally and to avoid a financier coming in with a lot of money and making all of the decisions, which is the case in the majority of media companies. And we also extended or own requirement for transparency to the public at large, since everything we communicate to our members can be found on our site.”

For practical reasons related to its management, the cooperative has two categories of members: “The 19 founders have all put in a higher amount than that required of the “normal” members and they also have more important duties. The founders are expected to invest and to adopt a position on Médor’s future strategies, whilst the members’ General Assembly (composed of 900 to 950 people) is there to validate our proposals, ask questions and stimulate further thought and reflections.”

Within the editorial team, “there are around ten journalists who are founder members. Five of this group are active on a very regular basis and they form a type of “steering committee” and take it in turns to be the chief editor. This is a model which we have invented, since we did not really like the traditional figure of a chief editor. The group of founders also includes graphic artists and me, although I look after the administrative side of things.”

We asked Tiffany if the cooperative form provides any particular advantage in terms of the freedom enjoyed by the journalists to deal with a subject and their relationship with their job. She tells us that: “when the journalists met in 2012 to talk about what was making them feel dissatisfied, they highlighted three main issues: money, time and freedom of expression.”

She went on to say that: “It had become impossible to tackle some issues in certain media companies. If one or another public figure just happened to be on the company’s board of directors, it was not possible to talk about them. Before we published an article, no other news outlet dared to speak about the Moreau case! (Editor’s note: Stéphane Moreau is a Belgian politician who is being prosecuted for misappropriation and embezzlement in two cases). Now the floodgates have been opened, but previously things were particularly difficult because he is an important public figure. You could say that he is a Walloon Berlusconi: he had placed people everywhere and this protected him from criticism in the media.”

When the journalists met in 2012 to talk about what was making them feel dissatisfied, they highlighted three main issues: money, time and freedom of expression.

“As for money and time, when we tried to estimate how much one issue of Médor would cost in order to prepare a financial plan, the reference we used was the cost of an investigation. The journalists estimated that its takes one full month of work to carry out an investigation in the field. We then added up the number of investigations per issue, with the shorter investigative pieces and other costs, and calculated the number of subscribers we needed. That it how we came up with the figure of 3,800 subscribers to help reach a financial balance.”

Médor’s future

Today, on average, Médor has 2,500 subscribers and sells 4,500 copies of each issue through bookshops. When asked how Médor is doing in 2018, Tiffany replies that, “now the challenge is to take things to the next level! At our last General Assembly, we decided to increase the level of risk, to make substantial investments, notably in terms of our content. To go a little further in what we propose as journalists and to try things that are not being tried elsewhere. Over the last few years we have run up a deficit. This is something which we will be able to overcome, but it does mean that we need to slowly increase sales, either by increasing the sale of each issue, which is something we are doing currently, or by developing another strategy which will generate a different financial income. The objective is to break even in 2022.”

“But yes, to answer your question, Médor is doing well because we have never had to make use of our capital, notably our members’ money, over the first few years. The reason we have decided to draw on this money now is to finance projects and to take the risks which we hope will pay off in a few years.”